In my continuing effort to acquire miscellaneous skills, I took up celestial navigation a little while ago. Yes, I mean using a sextant, some printed tables, and a rudimentary grasp of the principles of spherical trigonometry to find my position on Earth.

It’s unlikely anyone really needs to do this here in the 21st century, when we all carry GPS receivers in our pockets that are accurate to a few meters, but utility isn’t the only reason, or even the best reason, to learn things. I’ve wanted to understand how to use a sextant since I was a kid, watching my dad practice the skill from our yard. Back then, it was essential training for anyone who might sail out of sight of land, which was certainly a possibility for our boating-oriented family.

After reading some tutorials online, I checked out a half-dozen books on the subject from our local library system. The most useful by far were two by Hewitt Schlereth: Commonsense Celestial Navigation and Celestial Navigation in a Nutshell. The latter came out in the early 2000s, so it’s GPS-aware, while the former is from the pre-GPS era, and designed to function not only as an introductory textbook, but also as a complete standalone emergency navigation tool.

Reading about the subject whet my appetite to try it, so I called Dad to ask for sextant recommendations. Instead of telling me which one to buy, he packed up and sent his old Davis MK-25. I picked up some sight reduction tables and a Nautical Almanac and started finding myself.

If you decide to do this yourself, I recommend following a similar path: start with Schlereth’s older book, then get a plastic sextant; Davis has a couple of models that are significantly cheaper than the MK-25 but just as good for most purposes. Once you have the equipment, go outside and start shooting the sun. If, like me, you don’t live close to a good view of a sea horizon, the Davis Artificial Horizon works very well, or you can improvise with a pan of dark liquid such as motor oil. In either case, instead of bringing the sun’s image down to the natural horizon in the sextant, you just bring it down to touch the top of its own reflection in the artificial horizon.

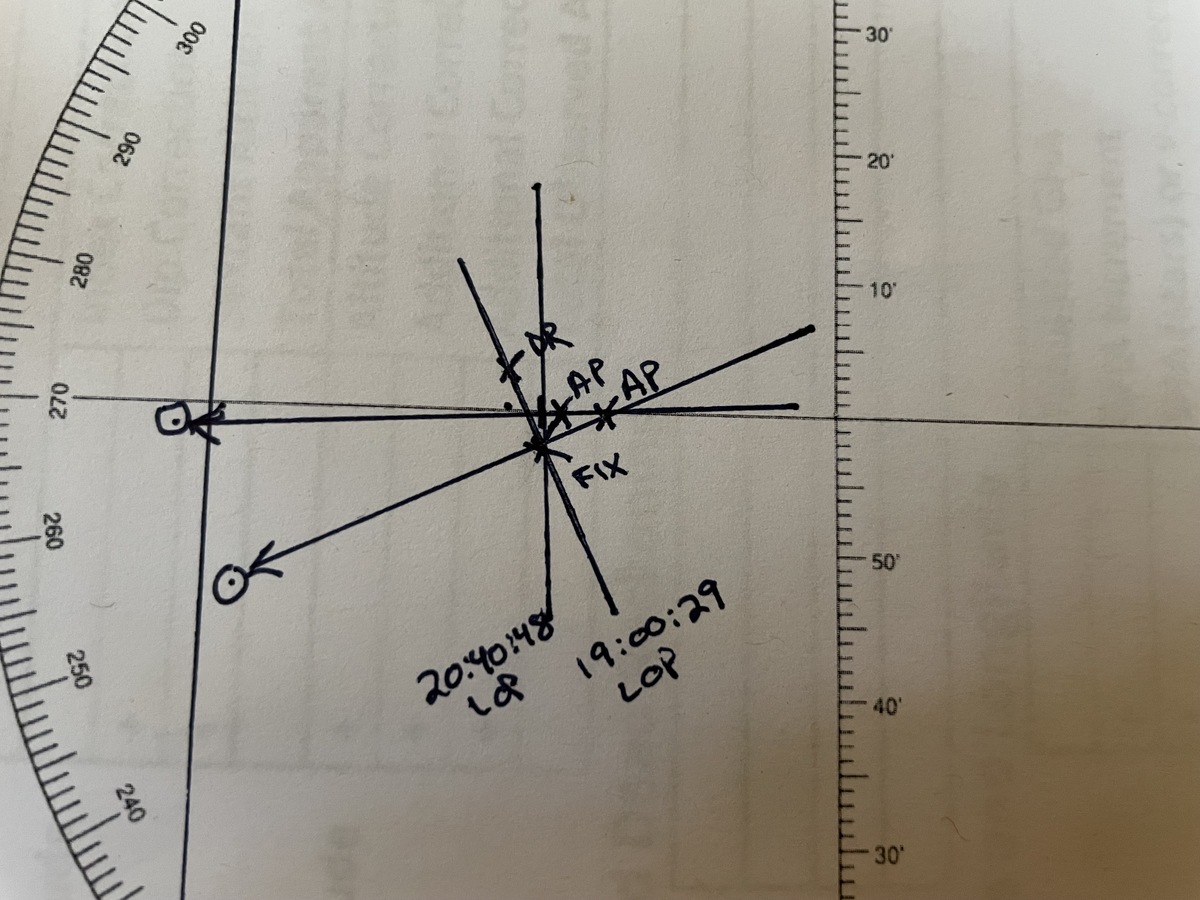

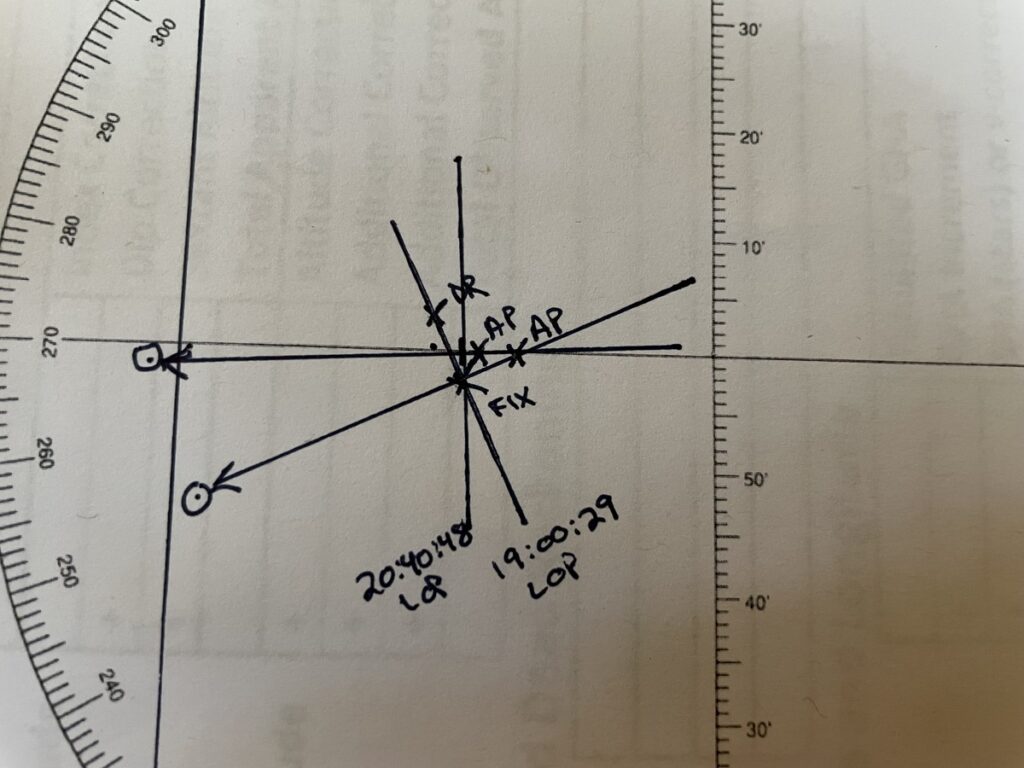

The other helpful item is a good worksheet. Reducing a sight only requires basic arithmetic, but there are a lot of steps to it, and forgetting to add one little correction can introduce a huge error in the final result.

After a few sessions, most of my lines of position now come within a few miles of where the GPS says I am. That may sound pretty bad by modern standards, where we’re accustomed to an electronic device knowing which side of a street we’re on, but for marine navigation it’s more than enough accuracy.

Of course, these relatively precise results are from sights taken from solid ground, and so far I’ve only shot the sun. The artificial horizon doesn’t reflect enough light to see stars and planets, and I haven’t had a good opportunity to try it on a lunar sight, but sun sights are the backbone of celestial navigation anyway.

I don’t envision using this skill at sea or in an aircraft cockpit anytime soon, but learning it has given me a much deeper understanding and appreciation of a bunch of cool subjects. Along with the sextant, Dad also sent a copy of The Last Navigator, Steve Thomas’s combination memoir, ethnographic study, and navigation manual, which documents how Polynesian navigators used the same principles to cross oceans long before the European Age of Discovery.

The skill of navigating by the sun, moon, and stars may be obsolete today, but it’s far from worthless.